The winter months are a peak time for the spread of infectious respiratory diseases. Cold weather often keeps people indoors, where it is easier for infections to spread.

Infectious respiratory diseases include the common cold, as well as other respiratory illnesses that can be more serious. Some people may be at increased risk of severe side effects from respiratory disease, including the elderly, children, and the immunocompromised.

Preventing the spread of respiratory disease helps keep everyone in your family and community safe. A few simple precautions can make all the difference. Once you know how these diseases are spread, you can take steps to contain them and make this winter a healthy one.

Airborne transmission

The most common way infectious respiratory diseases spread is by small aerosols that become airborne when an ill person coughs, laughs, talks, or sneezes. These tiny aerosols can hang in the air for hours and easily travel to the lungs when inhaled.

Surface transmission

Contact with a surface that is contaminated with droplets from an infected person is another route of transmission. If you touch something that has saliva or mucus on it and then later touch your mouth or face, you can become infected with the virus.

Close contact transmission

Being in close contact with someone infected with a virus can result in exposure to large virus-laden respiratory droplets. In contrast to the tiny aerosols that can hang in the air for an extended period, larger droplets fall quickly and most likely to spread when people are less than 3 feet apart.

Types of infectious respiratory viruses

* Chickenpox

* Coronavirus infections (including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV)

* Diphtheria

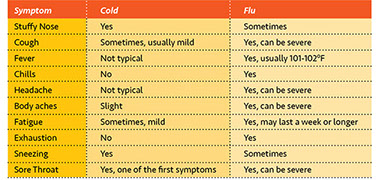

* Influenza (flu)

* Legionnaires’ disease

* Measles

* Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)

* Mumps

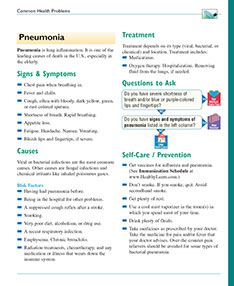

* Pneumonia

* Pneumococcal meningitis

* Rubella (German measles)

* Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

* Tuberculosis

* Whooping cough

Prevent the spread

* Minimize close contact with ill people.

* Wash your hands regularly with soap and water.

* Don’t share personal items such as food and utensils.

* Ask your doctor which vaccines are recommended for you, including the flu and COVID vaccines.

* Cover coughs and sneezes with your elbow and tissues (not your hands!).

* Stay home if you are ill.

_web381x254.jpg)

_web.jpg)